Sharper Images for Extreme LCLS Experiments

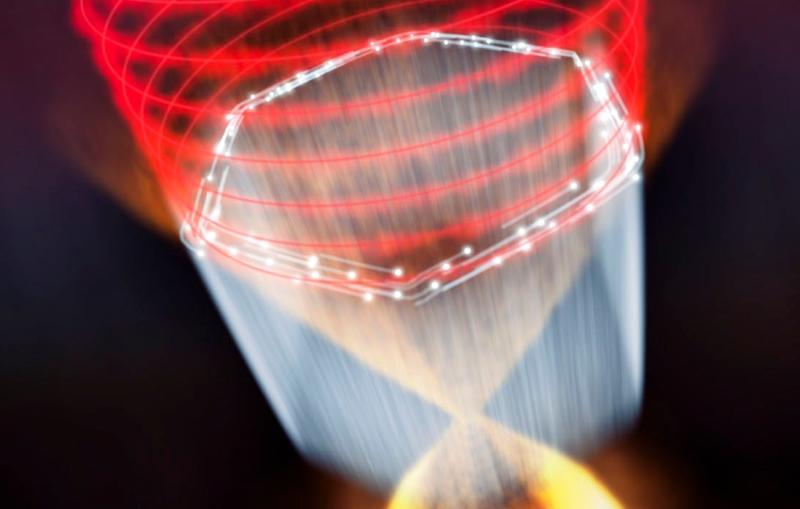

An imaging technique conceived 50 years ago has been successfully demonstrated at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, where it is expected to improve results in a range of experiments, including studies of extreme states of matter formed by shock waves.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

An imaging technique conceived 50 years ago has been successfully demonstrated at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, where it is expected to improve results in a range of experiments, including studies of extreme states of matter formed by shock waves.

The method, called ptychography (tie-KAW-grah-fee), was originally developed to capture data that was otherwise missing or difficult to collect in crystallography experiments, in which X-ray light scatters off crystallized samples to form diffraction patterns that reveal the sample's structure.

In recent years, ptychography has been rediscovered as a powerful tool for measuring the properties of X-ray beams and understanding imperfections in the focusing tools at synchrotrons and other X-ray research facilities, allowing scientists to better interpret and refine their data.

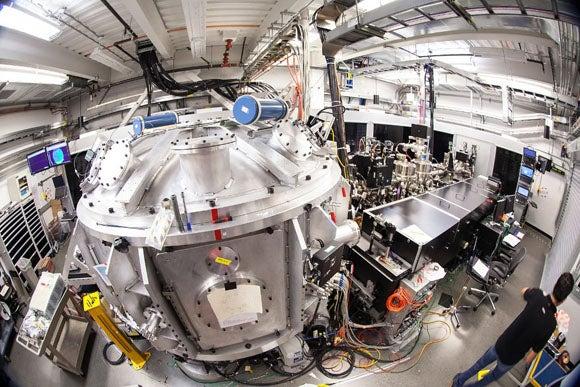

In experiments last year at the LCLS, researchers used ptychography to sharpen images made with the Matter in Extreme Conditions instrument, which specializes in transforming materials into ultrahot, ultradense states.

"For imaging it's very important," said Andreas Schropp, a visiting physicist who was the lead author of a paper focusing on the LCLS experiment, published April 9 in Nature Publishing Group's Scientific Reports. "Without it, you are not able to separate the properties of the X-ray pulses from the real features you have in the sample."

Schropp said he and other researchers at the PETRA III synchrotron in Hamburg, Germany, began to use ptychographic techniques to characterize the X-ray beams there about three years ago, and are now using the method routinely at the beginning of almost every experiment. "It was really a kind of revolution for us," he said.

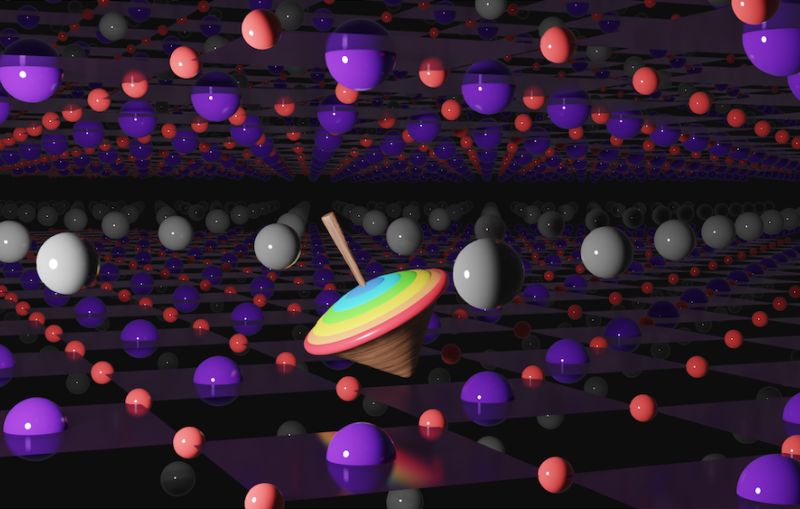

The LCLS precisely probes matter at the molecular and atomic scale, and is often used in combination with optical lasers that drive specific changes in materials.

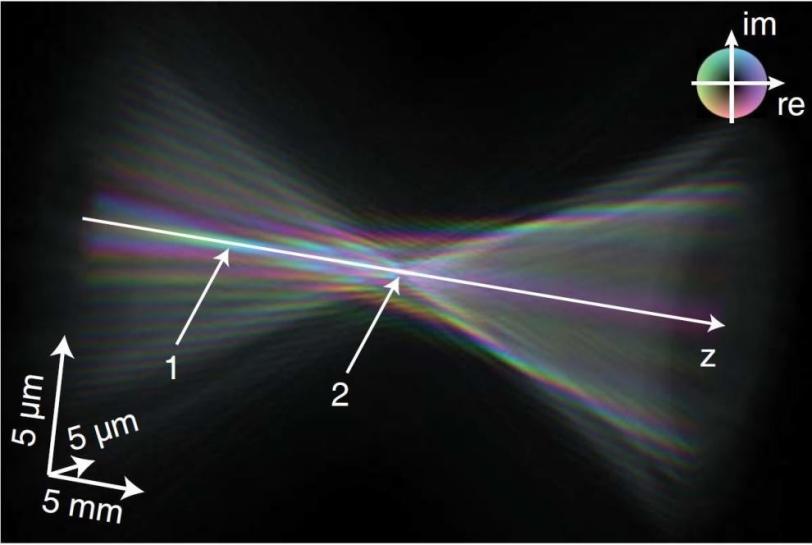

At the tiny scales the LCLS explores, it's important to know the properties of its X-ray pulses, such as variations in intensity in different areas of a focus, to improve the analysis of results.

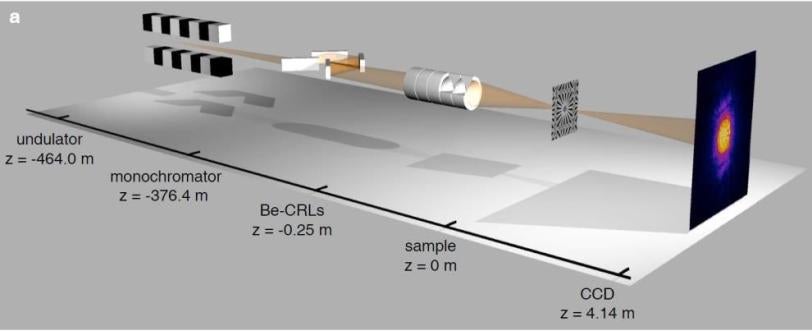

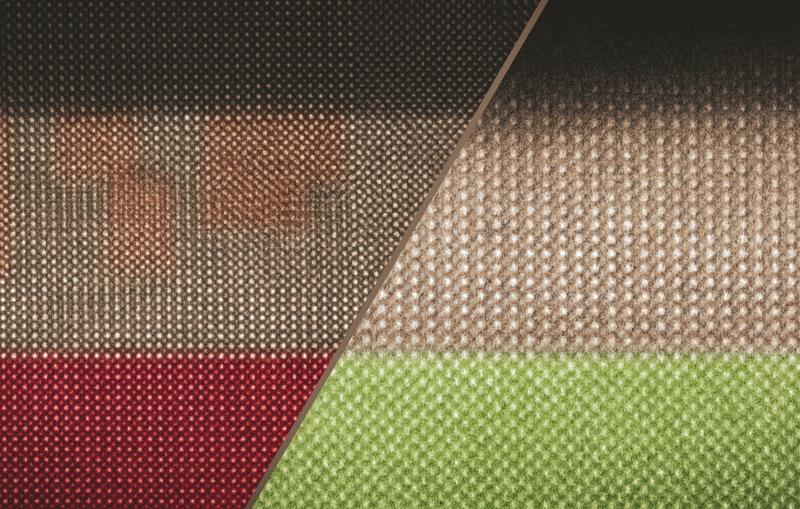

Researchers at LCLS did this with a tungsten plate with a very precise, nanoscale geometric pattern. They scanned it with a tightly focused X-ray laser beam, recording a diffraction pattern at each spot, and then used a sophisticated algorithm to reconstruct the geometric pattern of the tungsten plate and analyze the properties of the X-ray pulses.

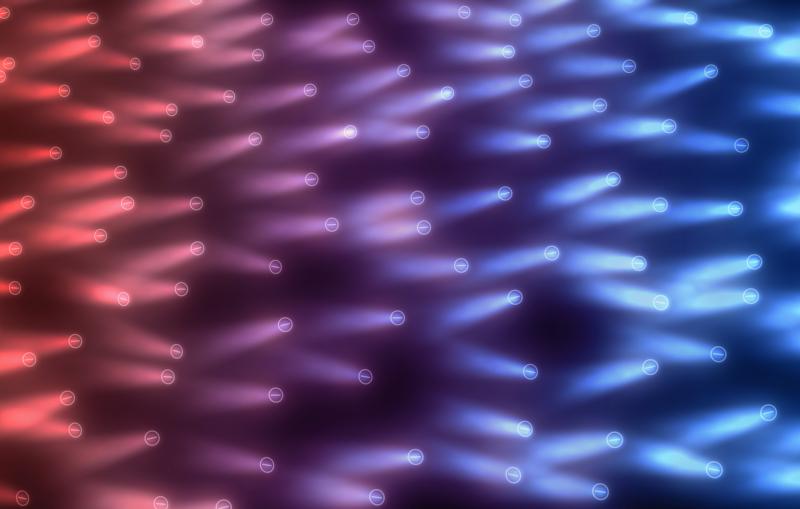

Like a flow of water divided into many separate channels by a shower head, the tungsten plate split up light of the X-ray pulses into a patterned array that yielded important details about pulse characteristics. By performing this kind of test before an experiment, researchers can better isolate the data for the effects they are trying to study, which is useful for producing higher-resolution images.

The technique also provides information on precisely what phase of the X-ray light waves – whether the peak, or trough, or somewhere in between – strikes the sample, which is useful in measuring the density of samples, for example, and producing high-resolution images. And it can pinpoint defects in the sophisticated focusing tools used in X-ray experiments.

At LCLS, ptychographic techniques could provide a faster diagnostic tool than another method, known as "imprints," that measures the dimensions of craters produced in materials by focused X-rays, Schropp said.

In principle, Schropp said, using this method with a fast detector at LCLS could provide valuable data about beam characteristics within minutes.

Experiments that create extreme states of matter and that require an understanding of intricate details of X-ray pulse intensity are among those that should benefit most from ptychography, Schropp said, and faster and higher-resolution detectors promise to refine the technique.

Schropp participated in an experiment at LCLS during the past week that imaged high-pressure shock waves in matter at high resolution, and used ptychography to sharpen those images by measuring X-ray beam properties.

The study was carried out by a team of researchers from SLAC, Dresden University of Technology (TU Dresden) in Germany, and the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden.

Citation: Andreas Schropp et al., Scientific Reports, 09 Apr 2013 (10.1038/srep01633).

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.